Canadian Seabirds Help Fight Microplastic Pollution

Canadian Seabirds Help Fight Microplastic Pollution

Environment and Climate Change Canada use indicator species like the northern fulmar to monitor microplastic pollution

“The only place where we have legislated plastic pollution monitoring and tracking is in the North Sea and it uses fulmars,” she explains.

“The only place where we have legislated plastic pollution monitoring and tracking is in the North Sea and it uses fulmars,” she explains.

Now, Dr. Provencher, and her team in the Ecotoxicology and Wildlife Health Division of Environmental and Climate Change Canada, examine northern fulmar stomachs in Canada to monitor plastic pollution levels in response to policy changes.

What is the Northern Fulmar?

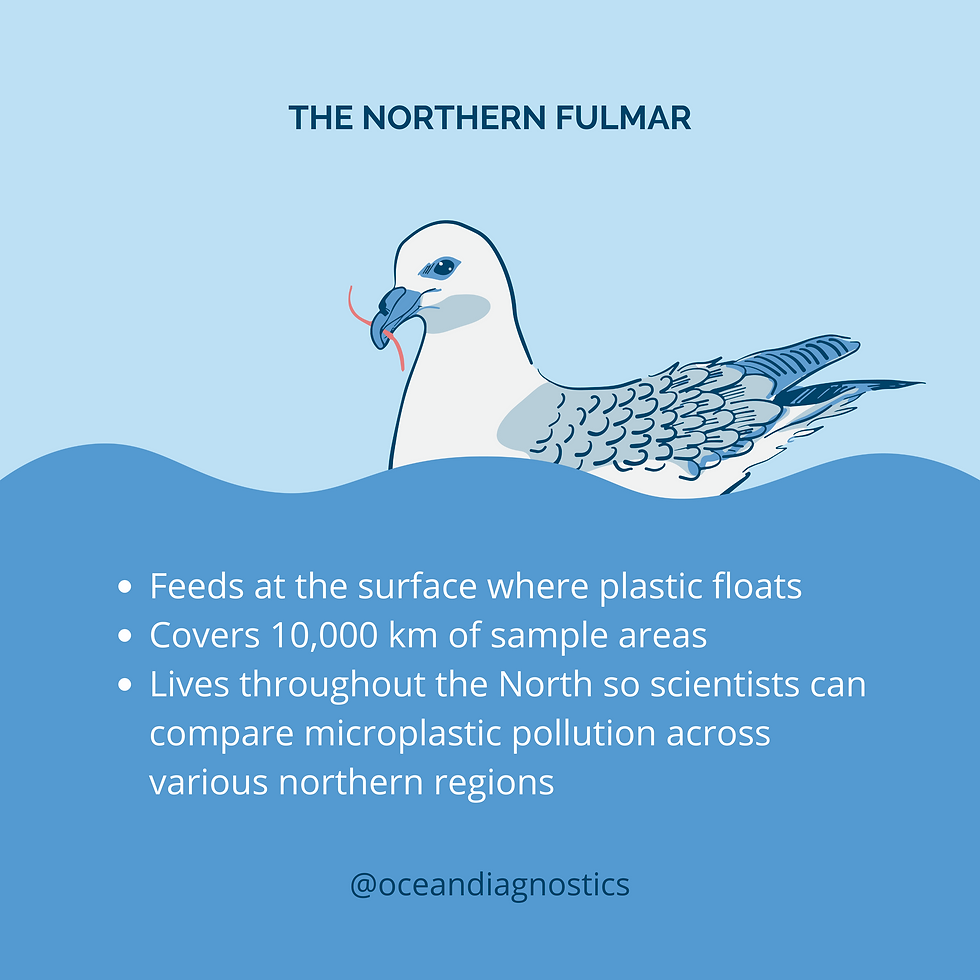

The northern fulmar is an indicator species, meaning they can indicate the level of microplastic pollution in areas they feed in

-

Fulmars are great indicator species to monitor plastic pollution.

-

They are limited to eat at the surface, where plastic floats.

-

Covering about 10,000 km, they sample huge areas just through their regular feeding habits.

Since northern fulmars reside in the Arctic, the United Kingdom, France and Germany, scientists can compare microplastic pollution across various northern regions. This comparison is important to weigh the effectiveness of plastic policies in different places.

“When collecting water samples, you get a measurement very specific to that place and time, which is good for certain questions,” Dr. Provencher notes. When considering the bigger plastic pollution picture however, “the birds essentially go in and do a bunch of surface water samples themselves.” That is what makes a great indicator species!

“Fulmars are one tool in the monitoring toolbox,” explains Dr. Provencher

The selected indicator species will largely depend on the research question we need answered. “For example, if we look at plastic pollution in terms of human health, we would pick a species that humans eat,” explains Dr. Provencher.

The goal is to start at the question and design monitoring programs to support it.

A harm reduction approach gives species the best chance at resilience

“Plastic pollution is a loss of a product to the environment...It is a huge issue. We need to regulate it because plastic pollution is not good for anyone,” states Dr. Provencher.

The challenge, she notes, is to determine where to start and what to prioritize. What plastic product, type or additives should government tackle first?

Also, while microplastics can leach chemicals and make animals feel full without adding nutritional value, microplastics themselves are not a singular issue.

“The threat of microplastics to fulmars is multifaceted. Plastic is not the only concern,” she explains.

While fulmars have been eating plastics for decades, they have also been battling several other stressors like bycatch or changing sea ice conditions.

“In a world of multiple environmental threats,” says Dr. Provencher, “we need to think of threats in a cumulative way.”

“In a world of multiple environmental threats,” says Dr. Provencher, “we need to think of threats in a cumulative way.”

To do so, Dr. Provencher looks to a harm reduction approach. “Borrowing from social work, harm reduction is about managing and removing all the things that can cause harm, so the population is more resilient,” she says.

It is about managing the contaminants you can reduce because other sources of stress may not be as easily managed.

Government research groups constantly stay on top of shifting prioritizes and environmental concerns

“We are kind of standing on quicksand.” – Dr. Provencher

“The evidence-based approach to prioritization is an iterative process,” explains Dr. Provencher, “we are kind of standing on quicksand.”

It is critical to be on top of new science to understand what the priorities are. For example, Dr. Provencher notes that only five years ago plastics in biosolids, which are applied to agricultural fields, was not on scientists’ radars. Now, they’re a priority.

Within government, there are typically two scientific groups: the policy group and the research directives.

The policy group receives data from the research group and presents this new data at conferences. After conferences, they then bring new ideas and priorities back to the research group.

The research group receives the feedback, priorities and news on what was discussed at the conference from the policy group, and then continues to conduct more research.

In this back-and-forth feedback loop, indicator birds like the northern fulmar provide the perfect plastic pollution tracking tool.

Public concern drives policy, which influences government research direction

The public also plays a key role in policy development and public concern has driven national and international environmental policies.

The public can influence policy by voting, through their purchasing decisions (like buying items with less plastic), and by advocating for evidence-based approaches to decision making. Using evidence of plastic ingested by the northern fulmar, scientists and the public can inform policy decisions.

With informed policy decisions, one day we may be able to buy products without worrying that they’ll end up in the stomach of our Canadian seabirds

While we have a lot of work left to do, Dr. Provencher is encouraged by our future generation. While wandering the grocery store aisles, her daughter asked for a bottle of pop. Dr. Provencher explained that she has found pop bottle lids in the stomach of seabirds. Now, every time she and her daughter are in the grocery store, her daughter (loudly) asks, "mom are you still finding pop lids in birds' stomachs?!" She has even brought the issue up to strangers buying plastic bottles. Now that she knows where the plastic can end up, she has lost the desire to have it.

Dr. Provencher hopes that one day we will stop finding plastic bottle caps in birds and that plastic will stay in the economy and not be lost to the environment. Until that day comes though, monitoring with indicator species will continue to take place.

Ocean Diagnostics Inc is an environmental impact company that develops technologies and laboratory capabilities to standardize microplastics data collection and analysis. The company works closely with academic and government partners to advance microplastic science. ODI has partnered with Environment and Climate Change Canada to share information on plastic pollution from Canadian plastic experts. Learn more here.

Follow #BeatPlasticPollution for the latest news.