Are microplastics banned in Canada?

For instance, there are regulations already in place that target specific subsets of microplastics, like the 2019 ban on microbeads in toiletries. There are also regulations being developed that focus on larger plastics that can generate microplastics when they accidentally end up in the environment.

To protect our health and our environment, documenting plastic pollution in the Canadian environment by community scientists, as well as public support, will be essential in further shaping regulations and evaluating their impacts, while also maintaining the momentum for positive change on plastic pollution around the world.

“In situations where plastics do not serve an essential purpose, there are opportunities to eliminate uses that generate unnecessary microplastic waste,” explains Dr. Anna Posacka Ocean Diagnostics Chief Scientific Officer.

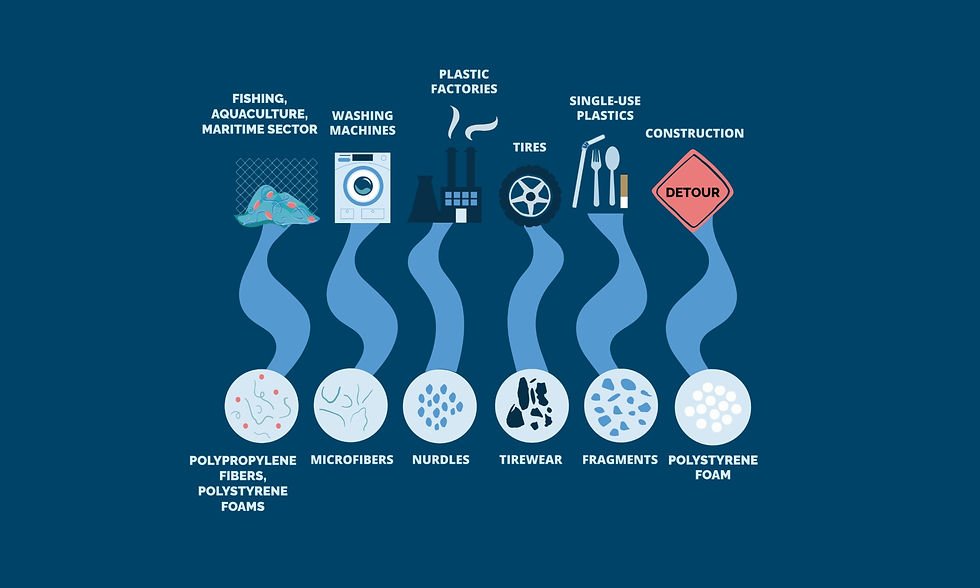

There are many sources of microplastics to consider

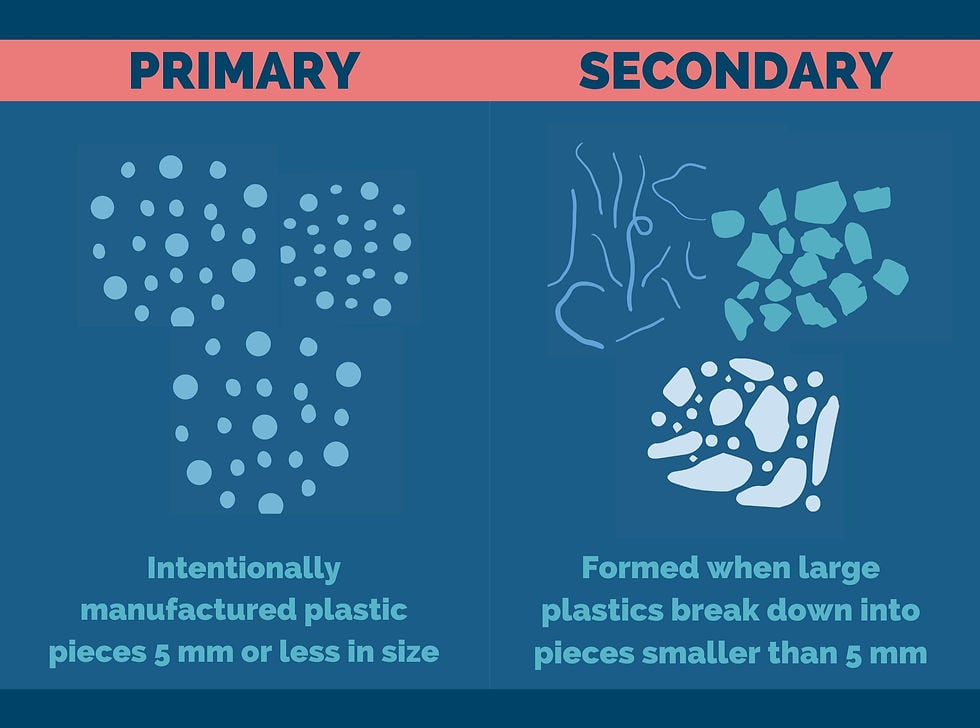

To understand regulations that address microplastic pollution, it is essential to understand that a variety of microplastics exist.

There are two classes of microplastics: primary and secondary. Primary microplastics are intentionally manufactured as plastic particles smaller than 5 mm. They are often used as abrasives or as pellets to form larger plastic items (i.e., “nurdles”). Secondary microplastics are formed from the weathering or fragmentation of larger plastic items, like consumer goods.

Both primary and secondary microplastics need to be considered in a holistic approach to regulating microplastic pollution in Canada.

Plastic pollution regulations in Canada

“In situations where plastics do not serve an essential purpose, there are opportunities to eliminate uses that generate unnecessary microplastic waste,” explains Dr. Anna Posacka Ocean Diagnostics Chief Scientific Officer.

In Canada, the actions taken thus far are limited to a few types of microplastics. For example,

-

In November 2018: Canada adopted a strategy for Zero Plastic Waste. Phase 1 began in 2019 and phase 2 in 2020.

-

In July 2019: Canada banned the sale and manufacturing microbeads in toiletries.

-

In May 2021: Canada added plastic-manufactured items to its list of toxic substances on the Canadian Environment Protection Act’s schedule 1.

-

In June 2022: Canada banned six single-use plastic items.

-

In February 2022: Canada launched a public consultation on a regulation that would require plastic packaging to contain at least 50% recycled content by 2030.

The types of microplastics addressed in these regulations include:

-

Primary microplastic pollution from microbeads in toiletries, which are addressed through the microbead ban.

-

Secondary microplastics formed from the breakdown of single-use plastics left in the environment, which are addressed through Canada’s single-use plastic bans and further Zero Plastic Waste initiatives.

There are more opportunities to cut unnecessary microplastic waste and the Canadian public is at the forefront of this change.

Example 1: Nurdles

Pre-production plastic pellets or “nurdles” are another group of primary microplastics. These can end up in the environment due to accidental spillage. They have been found by researchers and community scientists in Lake Ontario around Toronto, on Vancouver Island and around the world.

Currently, there are no targeted laws governing nurdle spillage, but actions to tackle this type of microplastic are being considered under the Canada action plan on zero plastic waste.

According to the UofT Trash Team, some plastic manufacturers have voluntarily committed to reducing their nurdle leakage, but voluntary action may not be enough.

Community members can help by assessing the presence of microplastics in their neighbourhood, engaging with decision-makers and in doing so further influencing policy and actions.

Example 2: Polystyrene Flotation

Canada works toward policy to reduce marine pollution from polystyrene floatation

Expanded polystyrene beads can form secondary microplastics when they break off large floatation devices in the marine environment. They have been found on many Canadian beaches and are challenging to clean up.

Our recent pilot study, fuelled by community science volunteers and a partnership with Environment and Climate Change Canada, revealed 81% of microplastic pollution on southern Vancouver Island sandy beaches, particularly near marinas, is polystyrene.

Given the hazard polystyrene poses to the environment, organizations like Surfrider Canada are taking the data from this community science study to the federal government.

[Sign their petition here!].

Becoming a community scientist is one actionable step you can take to fight plastic pollution. Should you find visible polystyrene or foam beads on your beach, you can collect this data and take it to policymakers using resources in our Community Science Toolkit.

There is more work to be done – you can help!

Community concern and scientific data led to the UNEP international agreement to address plastic pollution, but more action is needed

At an international level, there are currently no regulations specific to the mismanagement of microplastics. Globally, in March 2022, however, the United National Environment Assembly committed to the development of a legally binding agreement by 2024 to address plastic pollution.

Negotiations between the 173 nations begin on November 28, 2022.

Community science and microplastic collection add to the growing global evidence that microplastics are everywhere and action is needed to keep them out of our environment.

Reliable data collected by researchers and the public is key in further shaping microplastic pollution legislation and assessing our environment for signs of positive change.

With the right tools, you can start a project today and contribute data from your own community. The data you collect can prompt further regulations on microplastics and can help protect our environment from the threat of plastic pollution.

Plastics are not going away. The faster we act, the better.

We need compassionate community scientists to collect data needed to inform further legislation.

Get your Community Science Toolkit and collect data in your community.

Send what you find to your MP and ask for change.